Goodbye, Bull

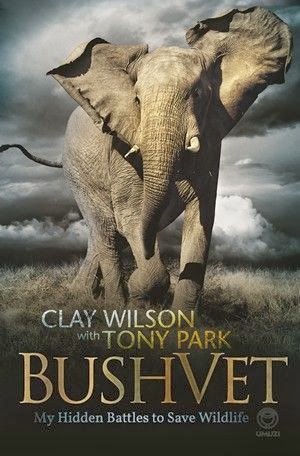

My mum paid me what I think is the ultimate non-fiction writer's compliment the other day. She said my latest book 'Bush Vet', by Dr Clay Wilson and me, read like a novel.

Mothers are not known for dishing the dirt on their writer children, and it would be a rare parent or other loved one that said 'this book is crap'. It's not that they don't offer frank assessments - if your nearest and dearest reader says something such as 'Hmm, I'm not so sure about that bit', then you know that's code for 'crap'.

To say a biography (co-written autobiography, in fact) reads like fiction might sound a like a bit of a back-hander, but it's not. It's what I aim for, to try and make my non-fiction entertaining as well as informative, perhaps interspersed with a bit of drama and tragedy.

Dr Clay Wilson, a South African-born American citizen, worked for a few years as a volunteer wildlife veterinarian in Chobe National Park on Botswana's northern border. When I first met Clay and his then girlfriend, Laura, Clay was a man literally living his dream.

He'd sold up his profitable veterinary practice in Florida and returned to his native Africa to do what he'd always wanted to do, work with African wildlife. He was passionate about animals, especially elephants, and he had plenty of work.

Chobe's home to about half of Africa's remaining elephants and it sits right next to the town of Kasane, which itself is close to the borders of Zimbabwe and Zambia. It's a busy tourist area and a hub for traffic moving through four countries (Namibia's close by, as well). There are too many elephants and too many people in too small an area and the end result is human-animal conflict.

The Chobe riverfront and surrounding arable areas have seen a massive increase in agriculture in recent years and the population of Kasane has grown. However, this area is not only a transit route for border traffic - elephants and other game also migrate to and from the river. Animals are skittled by cars and shot by angry farmers who resent elephants eating their crops and lions eating their cattle.

Botswana may have a reputation for being one of Africa's most stable democracies, with a high GDP and good employment, but that doesn't stop people still setting snares and shooting wildlife for bushmeat. Poorer people from neighbouring Zimbabwe, Zambia and Namibia are also on the hunt for ivory and food.

Much - too much - of Clay's work was dealing with the fallout of this never-ending conflict. He had to euthanise elephants that had been wounded by poachers or those that had ingested plastic bags through feeding from the local rubbish dump. He saw lions, endangered wild dogs, and hyenas knocked down and killed by speeding cars, and he had to finish off a magnificent male lion that had been left paralysed by a farmer's shotgun blast.

Amidst the day to day sorrow of Clay's job were the success stories, which kept him going. He saved a waterbuck that had been nearly electrocuted by an electric fence; he freed a baby elephant that had been stuck in the mud at a waterhole (he and the baby were nearly squished when he had to dart the calf's cranky mother and she toppled beside them); he nursed several magnificent birds of prey back to health after they were hit by cars or flew into power lines; and he treated scores, if not hundreds, of other animals injured by snares.

Clay's heart was in the right place but if he had fault (in fact he had quite a few - he was human) it was that his heart ruled him, not his head. He was quick to criticise the authorities and he was incapable of holding his tongue or acting diplomatically when he saw a problem. You don't hear much about problems in Botswana - poaching, crime, human-animal conflict - because that's the way the country likes it. Clay was chastised for having the temerity to talk about these issues on Facebook.

He put his life on the line more than once to protect wildlife - he joined an army patrol chasing poachers down the river in a boat, and got himself into a gunfight with ivory hunters who he surprised while they were still chopping out a dead elephant's tusks. One of the men who had killed the animal opened fire on Clay with an AK 47; Clay stood his ground and fired back with his own rifle.

Clay was, as my mum pointed out, just like an imaginary larger than life character in one of my books.

The main difference between Bush Vet, Clay's life story, and one of my novels, however, is that my books have (generally) happy endings. Clay's book did not.

I still don't know exactly why (and neither did he), but Clay's residency permit was cancelled and he was deported from Botswana. It was probably because he spoke out one too many times, and, true to his nature, called things as they were and not as the authorities wanted them to sound.

Clay was locked in gaol and eventually flown to the United States. He made a couple of trips back to Africa, to try and forge a new life and rekindle his dream, (after everything he owned was sold at auction by a distraught but courageous Laura back in Botswana). He tried Kenya, but nothing came of that, and he and Laura split up after she returned to the US.

Clay suffered from pancreatitis and while he told me, a couple of months ago, that the first bout had 'nearly killed him', I assumed, incorrectly, that he may have been exaggerating a bit. I was wrong. His subsequent relapses did result in his passing on December 20, 2013.

Clay's dream ended in a nightmare and to his dying day he was still telling friends in the US that all he wanted to do was to get back to Africa and save 'his' elephants. As his biographer I didn't like him referring to animals as 'his', but I think I may have been wrong to discourage this in his book.

The fact is that there are elephants, waterbuck, impala, buffalo, eagles, hyena, lions, leopards and even a tortoise (whose shell he super-glued back together after it had been run over) that are probably still alive today solely because of Dr Clay Wilson.

One of Clay's friends, TJ Thompson, described Clay on Facebook recently as a 'bull elephant in a China shop'. I cannot think of a better description for this man, and I am sure he would have appreciated it.

Clay's memorial service is this weekend, in Florida. I can't get there, but I will be thinking of him. In my mind, I'll ask my departed friend one final question: given everything that happened would you have still sold everything and gone to Africa to work as a vet if you knew what was to come?

I think I know what his answer would be.

Mothers are not known for dishing the dirt on their writer children, and it would be a rare parent or other loved one that said 'this book is crap'. It's not that they don't offer frank assessments - if your nearest and dearest reader says something such as 'Hmm, I'm not so sure about that bit', then you know that's code for 'crap'.

To say a biography (co-written autobiography, in fact) reads like fiction might sound a like a bit of a back-hander, but it's not. It's what I aim for, to try and make my non-fiction entertaining as well as informative, perhaps interspersed with a bit of drama and tragedy.

Dr Clay Wilson, a South African-born American citizen, worked for a few years as a volunteer wildlife veterinarian in Chobe National Park on Botswana's northern border. When I first met Clay and his then girlfriend, Laura, Clay was a man literally living his dream.

He'd sold up his profitable veterinary practice in Florida and returned to his native Africa to do what he'd always wanted to do, work with African wildlife. He was passionate about animals, especially elephants, and he had plenty of work.

Chobe's home to about half of Africa's remaining elephants and it sits right next to the town of Kasane, which itself is close to the borders of Zimbabwe and Zambia. It's a busy tourist area and a hub for traffic moving through four countries (Namibia's close by, as well). There are too many elephants and too many people in too small an area and the end result is human-animal conflict.

The Chobe riverfront and surrounding arable areas have seen a massive increase in agriculture in recent years and the population of Kasane has grown. However, this area is not only a transit route for border traffic - elephants and other game also migrate to and from the river. Animals are skittled by cars and shot by angry farmers who resent elephants eating their crops and lions eating their cattle.

Botswana may have a reputation for being one of Africa's most stable democracies, with a high GDP and good employment, but that doesn't stop people still setting snares and shooting wildlife for bushmeat. Poorer people from neighbouring Zimbabwe, Zambia and Namibia are also on the hunt for ivory and food.

Much - too much - of Clay's work was dealing with the fallout of this never-ending conflict. He had to euthanise elephants that had been wounded by poachers or those that had ingested plastic bags through feeding from the local rubbish dump. He saw lions, endangered wild dogs, and hyenas knocked down and killed by speeding cars, and he had to finish off a magnificent male lion that had been left paralysed by a farmer's shotgun blast.

Amidst the day to day sorrow of Clay's job were the success stories, which kept him going. He saved a waterbuck that had been nearly electrocuted by an electric fence; he freed a baby elephant that had been stuck in the mud at a waterhole (he and the baby were nearly squished when he had to dart the calf's cranky mother and she toppled beside them); he nursed several magnificent birds of prey back to health after they were hit by cars or flew into power lines; and he treated scores, if not hundreds, of other animals injured by snares.

Clay's heart was in the right place but if he had fault (in fact he had quite a few - he was human) it was that his heart ruled him, not his head. He was quick to criticise the authorities and he was incapable of holding his tongue or acting diplomatically when he saw a problem. You don't hear much about problems in Botswana - poaching, crime, human-animal conflict - because that's the way the country likes it. Clay was chastised for having the temerity to talk about these issues on Facebook.

He put his life on the line more than once to protect wildlife - he joined an army patrol chasing poachers down the river in a boat, and got himself into a gunfight with ivory hunters who he surprised while they were still chopping out a dead elephant's tusks. One of the men who had killed the animal opened fire on Clay with an AK 47; Clay stood his ground and fired back with his own rifle.

Clay was, as my mum pointed out, just like an imaginary larger than life character in one of my books.

The main difference between Bush Vet, Clay's life story, and one of my novels, however, is that my books have (generally) happy endings. Clay's book did not.

I still don't know exactly why (and neither did he), but Clay's residency permit was cancelled and he was deported from Botswana. It was probably because he spoke out one too many times, and, true to his nature, called things as they were and not as the authorities wanted them to sound.

Clay was locked in gaol and eventually flown to the United States. He made a couple of trips back to Africa, to try and forge a new life and rekindle his dream, (after everything he owned was sold at auction by a distraught but courageous Laura back in Botswana). He tried Kenya, but nothing came of that, and he and Laura split up after she returned to the US.

Clay suffered from pancreatitis and while he told me, a couple of months ago, that the first bout had 'nearly killed him', I assumed, incorrectly, that he may have been exaggerating a bit. I was wrong. His subsequent relapses did result in his passing on December 20, 2013.

Clay's dream ended in a nightmare and to his dying day he was still telling friends in the US that all he wanted to do was to get back to Africa and save 'his' elephants. As his biographer I didn't like him referring to animals as 'his', but I think I may have been wrong to discourage this in his book.

The fact is that there are elephants, waterbuck, impala, buffalo, eagles, hyena, lions, leopards and even a tortoise (whose shell he super-glued back together after it had been run over) that are probably still alive today solely because of Dr Clay Wilson.

One of Clay's friends, TJ Thompson, described Clay on Facebook recently as a 'bull elephant in a China shop'. I cannot think of a better description for this man, and I am sure he would have appreciated it.

Clay's memorial service is this weekend, in Florida. I can't get there, but I will be thinking of him. In my mind, I'll ask my departed friend one final question: given everything that happened would you have still sold everything and gone to Africa to work as a vet if you knew what was to come?

I think I know what his answer would be.

Comments

Rest In Peace Clay